[ad_1]

Like the crooked fingers of fairy tale witches, a fragmented ivory artifact discovered several years ago at an Ice Age excavation site in southwestern Germany is poised to be pointed. magical intention.

Similar items have been discovered across the continent over the past century, all leading to speculation about their purpose. Thoughts whittled down to dots and punctured became staves and scepters. Or it could be a flute, or a symbol of occult powers. Ritual and magical tools.

Nicolas Konard, an archaeologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany, and Fehr Lotz, an archaeologist at the University of Liege in Belgium, have a much more pragmatic view of the discovery of the baton, suggesting that it could be used to weave something. This suggests that it may have been used. Other than spells.

Now, the two researchers have presented a proof-of-concept demonstration that supports their hypothesis.

In 2015, Conard, Lotz, and a team of fellow researchers discovered 13 pieces of processed mammoth ivory in the Holle Fels Cave in the Ach Valley. This cave was occupied 40,000 years ago and was already famous for the discovery of what is believed to be the oldest known cave. A representation of the human figure.

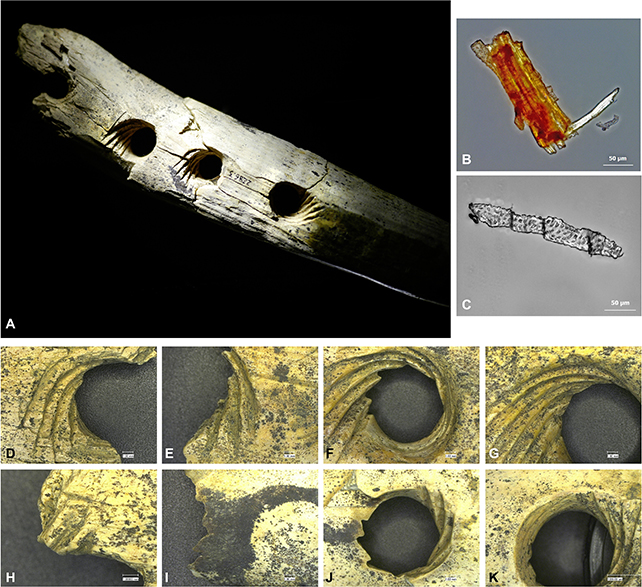

The pieces of ivory fit together perfectly to form an object 20.4 centimeters (about 8 inches) long, with four holes just wide enough for a pencil to fit through. The engineered ivory baton has no clear purpose, at least at first glance.

But thanks to its exquisitely preserved ditches and the plant fibers sifted from the surrounding soil, Conard and Lotz discovered that it was one of the Stone Age’s most valuable resources for making rope. I was convinced that it was a tool.

“This tool answers a question that has puzzled scientists for decades: how ropes were made in the Paleolithic era,” Lotz said in 2016.

Products such as stone, horn, and ivory can be preserved for thousands of years, while less durable materials like vegetable fibers are lost over time.

But rope, cord, and thread were important products in the Paleolithic period, used to tie and secure everything from packaging to weapons, food, and clothing. It is inconceivable that the technology to easily create such materials did not exist.

Further evidence that this artifact and a second, poorly preserved “perforated baton” (Lochstab in German) found downstream of the ruins of the Geissenkursterle cave were intended for making rigging. In order to do so, Conard and Lotz replicated their own Lochstab and put it to the test.

It was clear from the beginning that batons were neither practical nor necessary for making thin ropes or threads. Additionally, using the holes as guides allows you to twist thick cords of 2 to 4 strands quickly and efficiently.

Researchers tested a variety of materials, including deer sinew, hemp, flax, and nettle, and found that cattail, linden, and willow fibers produced the best results.

With four to five participants holding Lochstab replicas and feeding them strands, the researchers were able to weave five meters of strong, flexible, high-quality cattail rope in just 10 minutes. .

Like any reproduction, this experiment cannot prove beyond doubt that the artifacts served the same purpose or were necessarily used in the same way. After all, just because an ancient relic can be imaginatively used in fashion doesn’t mean it was ever used.

Similar objects may have slightly different uses, perhaps for holding a shaft while the firing point is fixed, or for straightening a length of wood.

Combined with microscopic analysis of the grooves and plant fibers at the Holle Fels Lochstab site, this may solve the mystery of how high-quality ropes were manufactured thousands of years ago.

This research scientific progress.

[ad_2]

Source link