[ad_1]

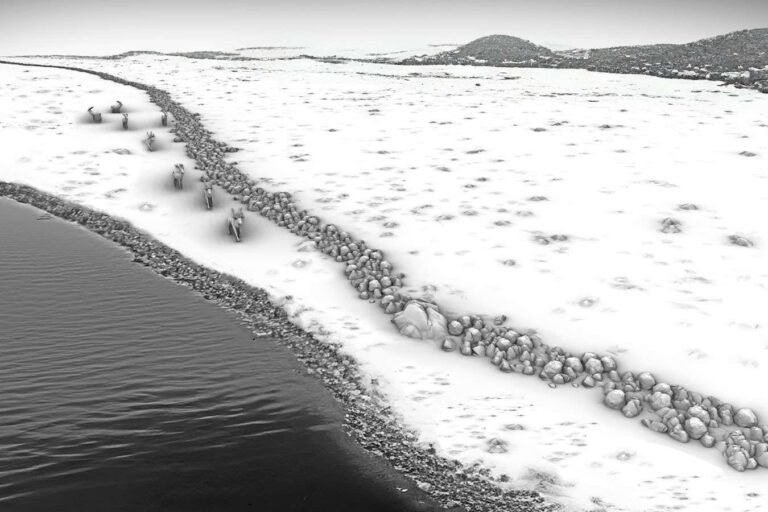

Graphical reconstruction of stone walls as hunting structures in glacial landscapes

Michał Grabowski

A low stone wall approximately one kilometer long has been discovered 21 meters below the surface of the Baltic Sea off the coast of Germany. The wall is believed to have been built around 11,000 years ago to guide reindeer to a more convenient place to kill them, and could be the largest Stone Age monument in Europe.

The discovery happened by chance. In 2021, students participating in a training session with geophysicist Jakob Gehrsen at Germany’s Leibniz-Baltic Sea Research Institute Warnemünde use multibeam sonar to map the ocean floor 10 kilometers offshore from the town of Relic. did.

“Then in the lab, we noticed some structures that looked unnatural,” Geersen says.

So in 2022, he and a colleague lowered a camera into the structure, revealing a row of stones. “It wasn’t until we contacted archaeologists that we realized it might be something important,” Geersen said.

Team member Marcel Bradmeler, an archaeologist at the University of Rostock in Germany, said there was no reason or evidence that modern structures were built underwater at the site. Nor does the team come up with any natural processes that could create such a structure.

This suggests that the wall was built when the area was dry, meaning it must be between 8,500 and 14,000 years old, Bradmeler said. Before that, the area was covered in ice sheets strong enough to destroy stone structures, but then rising sea levels submerged the area.

This wall runs along what was once a lake. It contains about 10 large rocks, up to 3 meters in diameter and weighing several tons, connected by more than 1,600 smaller stones, most weighing less than 100 kilograms. The stones are placed next to each other rather than one on top of the other, and the walls are less than 1 meter high in most places.

All the large stones are located where the wall has a zigzag bend. The researchers therefore believe that the structure was constructed by linking together larger stones that were too heavy to move and smaller stones that could be moved.

Professor Bradmeler believes it was probably made by hunter-gatherers from a culture known as the Kongemose culture, named after the Danish ruins where the stone tools and other artifacts were discovered.

The most likely explanation is that the structure was used to guide reindeer, he says. “The best-fitting hypothesis at the moment is a hunting drive wall.”

These hunter-gatherers are thought to have lived and moved in small groups, but when reindeer arrived in the area, they may have congregated in larger groups at the lake, Bradmeler said. he says.

Similar low walls, also called desert kites, have been found in many places in Africa and the Middle East, and even under the Great Lakes in North America. Some are up to 5 kilometers long, and it is now widely accepted that they were used for hunting.

These walls are usually low enough that animals such as antelopes can jump over them, but they usually avoid them when running in groups, said Marlies Lombard of the University of Johannesburg in South Africa, who discovered similar structures. . “In those situations, they tend to run parallel to obstacles such as low fences, rather than across them,” she says.

Most desert kites consist of two V-shaped walls to dislodge animals, but even a single wall can be an effective propulsion line, Lombard said. One possibility for the newly discovered wall is that it may have been used to drive reindeer into the lake and hunt them from boats, Bradmeler said.

There may also be a second wall covered in sediment nearby, Goesen said. He plans further research, including diving, to find direct evidence of Stone Age people, but so far researchers have been hampered by bad weather.

Other experts agree with their conclusions. “We think there is good evidence that the wall was an artificial structure designed to guide the movement of reindeer during migration,” said archaeologist Geoff Bailey of the University of York in the UK.

“Such discoveries suggest that large-scale prehistoric hunting landscapes may survive in a form previously seen only in the Great Lakes,” said Vincent Gaffney of the University of Bradford in the UK. he says. “This has a huge impact on areas of the coastal shelf that were previously habitable.”

Modern activities such as trawling, cable-laying and wind farm construction can destroy such sites, so more exploration is needed to find them before they are lost, Geersen said. Masu.

Bradmeler said no other structure of this type has been found in Europe. He believes that many of them once existed, but were likely destroyed by human activity.

topic:

[ad_2]

Source link