[ad_1]

Australia faces an intensifying extinction crisis. Since colonization, 100 native plants and animals have been officially listed as extinct due to human activities. The actual number is undoubtedly much higher.

Research shows Australians want to prevent extinction, regardless of the economic cost. But how much do we care when faced with a crisis?

In emergencies, there is a long-standing practice for public responders, such as firefighters, to first try to save lives, then property, infrastructure, and natural assets.

Our research published today investigated whether this treaty reflects the values of the community. We found that the people we surveyed value one human life more than the extinction of an entire non-human species. This is a fascinating and alarming result at the same time.

What are we willing to lose?

Catastrophic events force us to make difficult choices about what to save and what to give up. In such emergencies, our choices reveal in detail what value we attribute to different kinds of “assets,” including plant and animal species.

Our priorities will become even more important under climate change, which is causing more severe forest fires and other environmental disasters. If nature is always the last thing to be saved, we can expect repeated biodiversity loss, including extinction.

The unprecedented loss of biodiversity caused by the Black Summer fires was a harbinger of things to come. The fires destroyed the entire known ranges of more than 500 plant and animal species and at least half of more than 100 endangered species. The disaster wiped out at least one species of mealybug in Western Australia.

This loss caused us to reflect on our priorities. For example, the final report of the NSW Parliament’s inquiry into bushfires questions whether this hierarchy of protection should always apply.

Our new research investigated community values on this issue. The survey results were encouraging.

make difficult choices

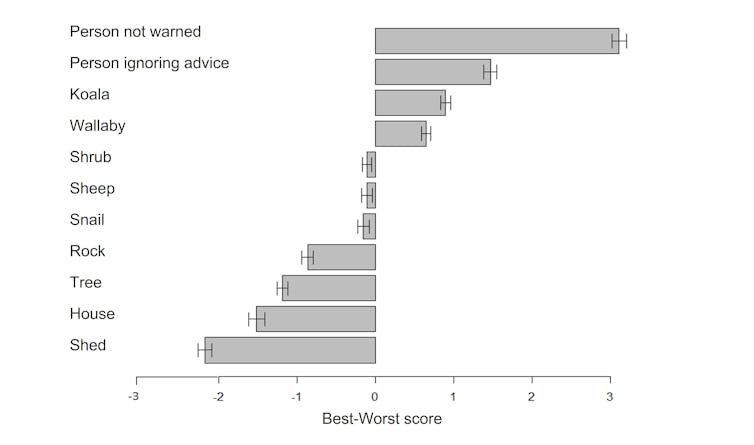

The survey involved 2,139 Australians. Respondents ranked the assets they would save in the event of a hypothetical wildfire by choosing from the following options:

- People who have not been warned to evacuate

- A person who ignored an evacuation order (and thus implicitly assumed responsibility for his or her own safety)

- 50 koala populations (many other populations exist elsewhere)

- One of only two populations of wallaby species

- Only native population of snail species (will become extinct if burned)

- Only population of native shrub species (will become extinct if burned)

- flock of 50 sheep

- house, shed, tractor

- Two items of Indigenous cultural significance: a rock art gallery and a wood carving.

Survey respondents overwhelmingly gave the two options the highest ratings for saving lives, even if that person was repeatedly told to evacuate, and even if snails and shrub species became extinct. I gave it.

Saving someone who did not receive an evacuation advisory was valued more highly than saving someone who ignored an evacuation advisory. The priority was then to save the koala population, followed by the wallaby population.

The remaining choices had negative scores. This means that respondents are more likely to choose the least important option than the most important option.

Among biodiversity assets, conservation outcome-based decisions will mean that preventing the extinction of snail and shrub populations is a top priority. Next up will be wallaby populations, followed by the relatively less impactful decline of koalas.

But the results were the opposite: people prioritized koalas over wallabies and were less interested in shrubs and snails. Ranking even lower were items of indigenous cultural significance. Preservation of houses and cabins was ranked lowest.

The results are clear

We draw several key messages from our findings.

First, the traditional hierarchy of fire protection, which prioritizes human life, infrastructure and biodiversity in that order, does not necessarily reflect societal values. In some cases, protecting natural assets is more important than protecting at least some infrastructure. During the Black Summer fires, attempts to rescue critical populations of threatened Wollemi pine showed that such protection of biodiversity assets is possible.

Second, our society values a single human life more than millions of years of evolution that could be lost almost instantly to the extinction of another species.

Third, our view of nature is far from egalitarian. In this case, the preference for saving koalas is consistent with previous research showing that we value iconic cute mammals far more than other species.

Fourth, animal welfare issues may take priority over consideration of conservation implications. We believe that the haunting images of koalas suffering in the Black Summer bushfires may have contributed to their being prioritized over species more at risk.

And finally, our results have implications for the conservation of little-known species that are increasingly becoming extinct around the world. These losses are largely ignored or undeplored by society.

This suggests that we need to better advocate for the conservation of such species. Australia’s invertebrate fauna is highly distinctive, fascinating and essential to ecosystem health. We must act now to prevent mass invertebrate losses.

Why not reconsider your priorities?

The world is becoming more and more dangerous. Much of the nature that surrounds us, sustains us and helps define us as Australians is at high risk of being lost.

We must think carefully about what kind of future we are leaving for our children and future generations. This requires you to rethink your priorities and, in some cases, make different choices.![]()

John Wojnarski, Professor of Conservation Biology, Charles Darwin University. Kerstin Zander, Professor of Environmental Economics, and Stephen Garnett, Professor of Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University. charles darwin university

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[ad_2]

Source link