[ad_1]

Research has revealed the Byzantine origins of silver in seventh-century European coinage, which was later replaced by Francia silver from Mele, marking a significant change in the economic and political framework of the Middle Ages. A selection of coins studied by the Fitzwilliam Museum, including coins from Charlemagne and Offa.Credit: Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Byzantine bullion facilitated the revolutionary introduction of silver coinage in Europe in the mid-seventh century.th A century later, it was overtaken by silver from Charlemagne’s Francia mines, new tests show. This discovery could change our understanding of Europe’s economic and political development.

Between 660 and 750 AD, Anglo-Saxon England experienced a major resurgence in trade, marked by a significant increase in the use of silver coinage, and moved away from its dependence on gold. Approximately 7,000 of these silver “pennies” have been recorded, an impressive number comparable to the total recorded during the entire Anglo-Saxon period from his 5th century to his 1066 AD.

For decades, experts have wondered where the silver in these coins came from. Now, a team of researchers from the University of Cambridge, the University of Oxford, and the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam has solved the mystery by analyzing the composition of coins in the collection of Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum.

journal ancient Today we will present the results of their research. Co-author Rory Naismith, Professor of Early Medieval English History at the University of Cambridge, said: “This silver may have come from Melle in France, an unknown mine, or it may have been melted down from church silver.” There was speculation.” . But there was no solid evidence to tell us that anyway, so we set out to find out. ”

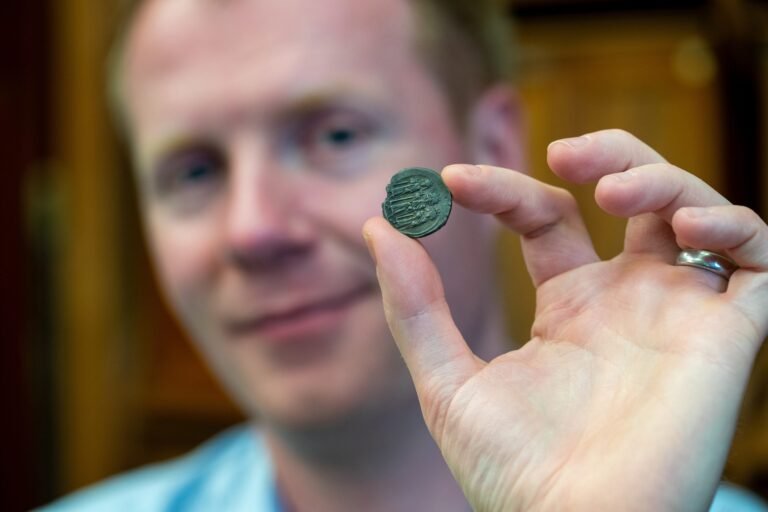

Professor Rory Naismith holds a Byzantine silver coin at the Fitzwilliam Museum.Credit: Adam Page

While previous studies have examined coins and artifacts mined at the Mele silver mine, Naismith and colleagues focused on less-studied coins minted in England, the Netherlands, Belgium, and northern France.

Fortunately, Naismith had the Fitzwilliam Museum, a “powerful center for early medieval numismatic research”, close by.

First, 49 Fitzwilliams coins (dating between 660 and 820 AD) were taken to the laboratory of Dr Jason Day at the University of Cambridge’s School of Earth Sciences for trace element analysis. The coins were then analyzed by “portable laser ablation,” which collects microscopic samples onto Teflon filters for lead isotope analysis. This is a new technology developed by Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam that combines minimally invasive laser sampling with the highly accurate results of traditional methods of taking physical samples of silver.

Although most of the coins contained silver, the proportions of gold, bismuth, and other elements in the coins led researchers to a previously unknown origin of the silver. Different ratios of lead isotopes within the silver coins provided further clues.

The analysis revealed two key findings:

1.Byzantine silver

Testing 29 coins from the early period (660 to 750 AD) minted in England, Frisia, and Francia, the researchers found three matching and very distinct chemical and isotopic signatures. discovered.rd to early 7th century silver from the Byzantine Empire in the eastern Mediterranean.

The silver is homogeneous across coins, characterized by high gold values (0.6-2%) and consistent isotope ranges, with no significant regional differences between coins. There are no known European ore sources that match the elemental and isotopic signatures of these early silver coins. There is also no meaningful overlap with late Western Roman silver coins or other objects. These coins are not recycled late Roman silver.

Naismith said: “This was a very exciting discovery. I proposed a Byzantine origin 10 years ago, but I couldn’t prove it. Now we know that Byzantine silver dates back to the 7th century around the North Sea. For the first time, we have archaeological confirmation that it was the main source behind a huge surge in minting and trade.”

Dr. Jane Kershaw, lead author of the study, said: oxford university“These coins are one of the first signs of a revival of the Nordic economy since the end of the Roman Empire. They show deep international trade links between what is now France, the Netherlands, and Britain. Masu.”

The researchers stress that this Byzantine silver must have entered Western Europe decades before it melted, as trade and diplomatic contacts were low in the late 7th century.

Mr Naismith said: “The elites of England and France were almost certainly already sitting on this silver coin. Very famous examples of this include the silver bowl discovered at Sutton Hoo and the Staffordshire Treasury. There are some ornate silver objects in there.

Together, the Sutton Hoo Byzantine silver objects weigh just over 10kg. If they had been melted, about 10,000 initial pennies would have been produced.

Kershaw said: “These beautiful objects of fame were only to be melted down when a king or lord urgently needed large sums of cash. Some major social change would have occurred.”

“This was quantitative easing, where the elites were liquidating resources and pumping more and more money into circulation. It would have had a huge impact on people’s lives. They were thinking more about money than before, and they were putting more and more money into circulation. There would have been more money-based activities that involved a much larger segment of society.”

Naismith wants to understand how and why so much silver moved from the Byzantine Empire to Western Europe. He suspects a mix of trade, diplomatic payments and Anglo-Saxon mercenaries serving the Byzantine army. This new discovery also raises interesting questions about where and how the silver was stored, and why its owners suddenly decided to turn it into coins.

The second major discovery of this research later revealed the transition from Byzantine silver to new sources.

2. The rise of frank silver

When the researchers analyzed 20 coins* from the latter half of this period (750-820 AD), they found that the silver was significantly different. It contained low levels of gold, which is now the most distinctive feature of silver mined at Mel in western France. Previously obtained radiocarbon data shows that mining at Mele was particularly concentrated during his eight years.th and 9th For centuries.

This study proposes that mele silver penetrated regional silver stocks from around 750 onwards and was mixed with older, higher quality gold stocks such as Byzantine silver. Coins minted in the regions closest to Mele had the lowest percentage of gold (less than 0.01%), while in the farthest reaches of northern and eastern France, the percentage rose to 1.5%.

Although it was already known that Mele was an important mine, it was not clear how quickly the site became a major player in silver production.

“We now know that after the Carolingians came to power in 751, Mele became a major force throughout Francia and increasingly in England,” Naismith said.

The study argues that Charlemagne caused this very sudden and widespread rise in the price of melee silver as he tightened his control over how and where the kingdom’s coins were made. Detailed records from the 860s state that Charlemagne’s grandson, King Charles the Bald, reformed the coins and gave every mint a few pounds of silver as a float to start the process. “I strongly suspect that Charlemagne did something similar with Mele Silver,” Naismith said.

Control of the silver supply went hand in hand with other changes introduced by Charlemagne, his sons, and his grandsons, such as changing the size and thickness of coins and inscribing names and likenesses on coins.

“We can now tell more about the circumstances in which these coins were made and how silver was distributed within and outside Charlemagne’s empire,” Naismith said.

england and francia

This discovery provides new context for the delicate diplomatic relationship between Charlemagne and England’s King Offa of Mercia. Like Charlemagne, Offa played an active role in silver trade and currency control. Both kings believed that trade and politics were inseparable. In an extant letter sent to Offa in 796, Charlemagne discusses merchandise trade and political exiles. The two also resorted to a trade embargo when their marriage negotiations failed.

Naismith said, “There was a lot of communication and tension between Charlemagne and Offa. Offa wasn’t in the same league, his kingdom was much smaller, he had less power over the kingdom, and he certainly didn’t have as much silver.” There weren’t many. But he remained one of the most powerful men in Europe, which was outside Charlemagne’s control. So they maintained a semblance of equality. Our findings show that the British It further strengthens the power relationship that France and France have had for a very long time.”

Mr. Naismith had no doubt that the British people would have been well aware that their silver was coming from Francia, and that they were dependent on it.

“When a product exists in limited quantities and in certain places, questions of power and national interest always come into play,” Naismith said. “In the early Middle Ages, this transcended borders and involved not only the rulers. Merchants, the Church, and other wealthy people all had an interest. The rulers were more directly involved. This behavior was new at this time.”

Reference: “Byzantine Plate and Frankish Mines: The Provenance of Silver in Northwestern European Coinage during the Long Eighth Century (c. 660–820)” by Jane Kershaw, Stephen W. Merkel, Paolo Dimpolzano, and Rory Naismith, 9 2024 April ancient.

DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.33

[ad_2]

Source link