[ad_1]

A new discovery off Australia’s northwest coast has rewritten the history books. Until now, the academic consensus was that pottery was brought to Australia by Europeans. This has now been proven wrong.

This new discovery shows that Australians were making ceramic products long before Europeans arrived. In fact, thousands of years ago, an archaeologist discovered numerous pottery shards that date back 2,000 to 3,000 years.

It is the oldest pottery ever discovered in Australia, and was discovered just 50 centimeters (20 inches) below the surface on an island located off the coast of Cape York Peninsula. Geological analysis of these pottery suggests that they were made locally, utilizing clay and tempering sourced directly from Jigur (also known as Lizard Island).

So if not from Europeans, where did Australians learn how to make pottery?

Cross-cultural exchange

In a recently published paper, Quaternary Science Review, a comprehensive report revealed the discovery of 82 pottery shards, all from isolated excavation sites found on this Great Barrier Reef island. This period of pottery coincides with the time when the Lapita people of southern Papua New Guinea were famous for their pottery making skills. This correlation certainly suggests potential cultural exchange and influence between these communities.

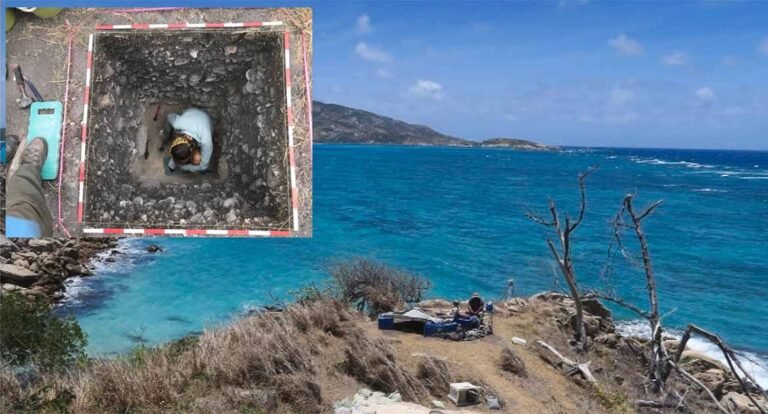

Laser scanning is carried out on site to preserve field data (Science Direct / Ian J. McNiven)

Professor Ian McNiven from Monash University said in a press release: “There is evidence of a history of deep connectivity across the Coral Sea, facilitated by advanced canoe navigation and ocean navigation technology, and the outdated concept of Indigenous isolation. “This is contradictory,” he said in a press release. “These discoveries not only open a new chapter in Australian, Melanesian and Pacific archaeology, they also challenge colonialist stereotypes by highlighting the complexity and innovation of Aboriginal communities. There are also things.”

During excavations, researchers found remains of shellfish and fish, evidence of food collected and consumed by the island’s ancient inhabitants more than 6,000 years ago. Dzigur is now established as the oldest known offshore island settlement within the northern region of the Great Barrier Reef.

These pieces are not only the oldest positively dated pottery discovered in Australia, but also link Indigenous Australians to a vast network of maritime communities stretching from Papua New Guinea to the Torres Strait and the Pacific Islands. It represents a complex web of trade and cultural exchange. This paper emphasizes the existence of a vibrant “cultural community beyond the Coral Sea.”

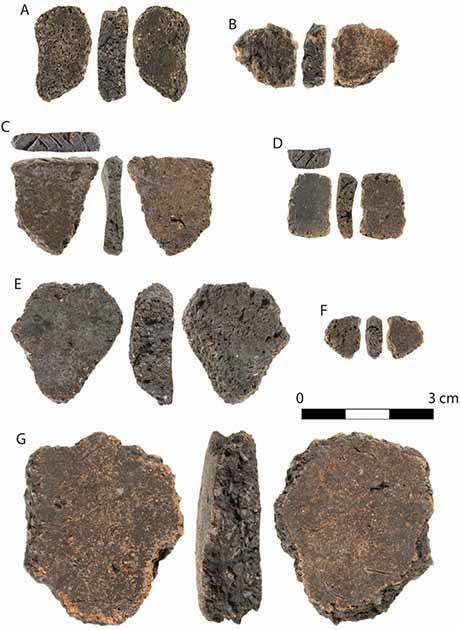

Some pottery shards were recovered from the ruins. Although they may be too small to tell how they were originally formed, we do know that they were manufactured using local resources, and that they pre-existed the arrival of Europe and are therefore part of Australia’s We know that we have rewritten history (Science Direct / Steve Morton)

Archaeologists say these discoveries require a rethinking of cultural exchange across the Western Pacific. This discovery marks the beginning of deeper insight into the region’s rich tapestry of ancient maritime civilizations.

Understand the production process

The process of understanding how these vases were made and their original appearance remains a major challenge. The debris is fragmented, with an average size of less than 2 cm (1 inch), making it difficult to deduce its full shape and function.

Kenneth MacLean, a member of the Dingar Nation and chairman of Walumbar Aboriginal Corporation, said: “Working with archaeologists and traditional owners on country is something that has never been done before for my people. And we work together on Country, we share each other’s stories about Country, and we not only share this story scientifically from our people, our elders, and our archeology side, but it’s our This is a good result that we can see. Together we can protect this country.”

These pottery shards may be small, but the stories they tell are certainly vast, which, as Ulm pointed out, is why the research journey took years to culminate in publication. explained. They needed to be convinced of that, because the excavation, which began in mid-2017 and lasted 14 months, confounded prevailing academic opinion.

The site itself has been known for only about 20 years. The first sighting of pottery shards at Dzigur was made in 2006 by an archaeologist from New Zealand on vacation while snorkeling in a shallow lagoon.

Efforts to pinpoint the exact age of these pottery shards initially proved inconclusive, but many scholars interpret them as concrete evidence of the Lapita presence in Australia. did. Originating from the islands of eastern Papua New Guinea, the Lapita people and their descendants embarked on large-scale migrations across remote regions of Oceania over several centuries.

In addition to their unique pottery, they introduced pigs, dogs, chickens, taro, and breadfruit to various regions, extending their cultural and agricultural influence to the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa. It is reported that it did. guardian.

Researchers believe the discovery of ancient pottery on the Great Barrier Reef may contain artifacts associated with the Lapita culture, which is scattered across the vast and largely unexplored coastline of north-east Queensland. We hope that this suggests the possibility of the existence of additional ruins.

This discovery highlights the exciting prospect of discovering further evidence that could significantly enrich our understanding of the region’s ancient maritime civilizations and their interconnectedness.

“These networks facilitated the exchange of goods and ideas between coastal communities in Australia and New Guinea over the past 3000 years. “While some objects indicate sharing, other objects, such as pottery, suggest sharing of technology,” the researchers concluded.

Top image: The Diguru excavation site where the discovery of ancient pottery rewrote Australian history. sauce: Science Direct / Ian J. McNiven.

Written by Sahil Pandey

[ad_2]

Source link