[ad_1]

(Bloomberg) — For years, the company was best known as Japan’s CLO whale: a $357 billion investment giant with an insatiable appetite for yield in an era of ultra-low interest rates.

Most read articles on Bloomberg

The Norinchukin Bank is now one of the biggest casualties in a very different financial world, where a long period of high borrowing costs is hurting the market’s weakest banks.

Agricultural Bank of Japan surprised markets this week by saying it would sell $63 billion in low-yielding U.S. and European government bonds after soaring short-term funding costs made it unprofitable to hold them. The privately held bank warned that its losses this fiscal year could balloon to 1.5 trillion yen ($9.5 billion), triple the forecast made less than a month ago.

While Norinchukin and the Japanese government have expressed confidence in the bank’s ability to weather the losses, the incident is a reminder of dangers still lurking in the financial system, 15 months after the collapse of SVB Financial Group Inc.’s Silicon Valley Bank.Suggestions by the Federal Reserve and other central banks that they are in no rush to cut interest rates have perplexed many investors who had been hoping for more aggressive action.

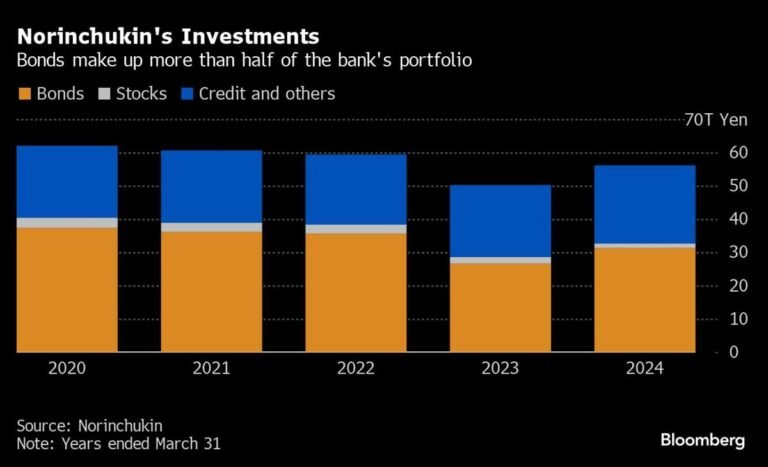

That’s creating a tricky situation for financial institutions like Norinchukin, which invested heavily in U.S. and European government bonds on hopes that lower interest rates would spark a rise in debt after two years of declines. The bank is now reviewing its portfolio, selling a third of its government bond holdings and shifting to other types of assets such as collateralized loan obligations and domestic and foreign bonds.

“I’m surprised they didn’t hedge their interest rate risk,” said Philip McNicholas, Asia sovereign strategist at Robeco Group Inc. in Singapore. “They have high conviction in the Fed and ECB rate cuts and may have initially thought this was a temporary postponement.”

Norinchukin Bank isn’t the only bank to suffer from misjudging interest rates. SVB collapsed early last year after the value of its huge portfolio of long-term bonds plummeted as interest rates soared. The losses triggered a run on deposits that eventually spread to other regional banks, including Signature Bank and First Republic Bank.

More recently, a prolonged period of high interest rates has left many banks and fund managers with losses on their books. The Fed has yet to act this year, even though markets were pricing in a 150 basis point rate cut in December. U.S. banks were carrying $516.5 billion in unrealized losses in their securities portfolios as of the end of March, according to regulators.

Western Asset Management, a $385 billion bond giant based in California, has had one of the worst-performing funds in the market as managers stuck to their view that longer-dated bonds will rise as the Fed gets closer to cutting interest rates.The firm’s Core Plus fund has outperformed its peers by just 3% this year and over the past three years, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Norinchukin Bank is at much lower risk of a deposit run because of its stable of agricultural cooperative clients, but questions are growing about how it mismanaged its liability portfolio and why its expected losses swelled so quickly.The bank’s spreads widened on Wednesday after reports of wider losses, but a top Japanese government spokesman said the bank’s health was safe.

“To be honest, I was surprised” by the size of the potential losses, said Ouchi Makiko, head of finance and general affairs at the Iwate Prefectural Shinkin Federation of Agricultural Cooperatives, a regional group that manages deposits for local cooperatives.

Junichi Matsuda of the Kyoto Prefectural Forestry Association said he had not been informed by Norinchukin of the recent events. If the bank were to request additional funds to cover its growing losses, “it would be a big shock,” Matsuda said, adding that it was unlikely. Norinchukin announced last month that it would raise 1.2 trillion yen from agricultural and other cooperatives it owns.

The century-old bank has shaken up markets before. In 2009, during the global financial crisis, it suffered Asia’s largest realized and unrealized losses on asset-backed securities, forcing it to raise 1.9 trillion yen. Norinchukin Bank serves as the central financial institution for Japan’s roughly 3,300 agriculture, forestry and fishery cooperatives. The bank accepts deposits from the cooperatives, rather than directly from farmers, and manages the funds through medium- to long-term investments.

An Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Ministry official said that together with the Financial Services Agency, “we will continue to closely monitor the bank’s business situation.” The bank’s unrealized losses are reflected in its capital adequacy ratio and do not affect the bank’s soundness, a company spokesman said in an email on Wednesday. The bank said Thursday that it does not need any additional funds beyond its planned capital increase.

The spokesman also said the company will diversify revenue sources between domestic and overseas assets depending on market conditions to build an optimal portfolio.

Even if Norinchukin Bank (as it is called in Japan) can shift to other assets, the problem of expensive dollar funding will remain. The bank says its JGB investments are mainly funded through repo funding.

The bank said adding collateralized loan obligations or corporate bonds would allow it to take on credit risk instead of interest rate risk. As of March, it held 7.4 trillion yen of CLOs. It also said it was considering investing in Japanese government bonds as it looks to restructure its securities portfolio.

Corporate bond spreads widened in June after the Federal Reserve turned out to be more hawkish than many investors expected, and repayment risks remain among weaker borrowers amid signs of an economic slowdown. Global corporate bonds are generating 1.31% excess returns over Treasuries in 2024, according to a Bloomberg index, down from a high of 1.74% at the end of May.

Still, Norinchukin Bank said it would gradually sell $63 billion in bonds through the end of its fiscal year in March, meaning it could mitigate losses if interest rate cuts later this year push government bonds higher.

Norinchukin has little room to invest in stocks, which are riskier and require more capital than other assets under Basel III banking regulations. As of March, only about 2.3% of the bank’s investments were in equities.

The tough shakeup now falls to Chief Executive Officer Kazuhito Oku, a company veteran who has already signaled management’s intention to cut his compensation and has no plans to step down anytime soon.

“There are several ways to take responsibility,” Oku told reporters last month after first warning of impending losses. “One is to resign, and the other is to complete my duties. I would like to choose the latter.”

–With contributions from Hisashi Sano, Russell Ward, Finbar Flynn, Tom Maloney and Serena Ng.

(Adds comment from Norinchukin Bank from the 14th paragraph onwards)

Most read articles on Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg LP

[ad_2]

Source link