[ad_1]

During Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet’s state visit to France in January, President Emmanuel Macron pledged support for the return of more Khmer artifacts and technical assistance for the expansion of the National Museum of Cambodia.

Macron is the first European leader to give voice to long-standing demands for the return of antiquities from Asian countries, since he said in a 2017 speech that he would “do everything” to return cultural heritage. is often cited as Heritage looted by colonial France.

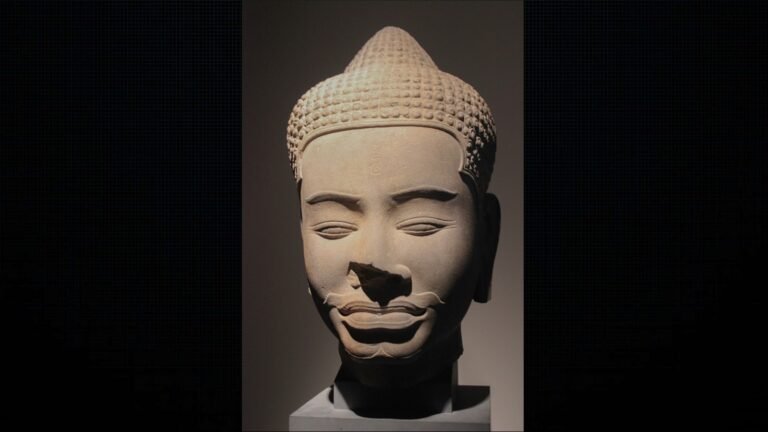

A few months ago, France’s National Museum of Asian Art, the Guimet Museum in Paris, agreed to return to Cambodia the head and torso of a 7th-century Khmer statue taken in the 1880s on a five-year loan. agreement.

In 2017, Berlin followed suit and agreed to return artifacts collected during the early 20th century genocide to the southern African nation of Namibia.

Last July, two Dutch museums, including the Rijksmuseum, returned hundreds of works of art to the former Dutch colonies of Indonesia and Sri Lanka.

“These items were illegally brought into the Netherlands during the colonial period and were obtained through extortion and plunder,” the Dutch government said in a statement.

In 2022, Naturalis, a natural history museum in Leiden, the Netherlands, will collect 41 prehistoric human specimens collected in the late 19th century from the remains of a village in northern Malaysia that is thought to date back 5,000 to 6,000 years. The remains were returned. .

Museum considers returning looted items

In January, the German and French governments agreed to spend 2.1 million euros ($2.27 million) to review African heritage in national museum collections, with similar plans possible for Asian artefacts. There are rumors that they have sex.

New calls for the return of stolen antiquities began in December, when New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art sent 14 sculptures it had purchased from indicted British art dealer Douglas Latchford to Cambodia and two to Thailand. announced that it would be returned. In 2019, looted antiquities were trafficked.

Brad Gordon, legal adviser to Cambodia’s Ministry of Culture and the Arts, who played a key role in repatriating the artifacts last year, said he was in contact with museums in Britain and Paris about the extensive Cambodian antiquities collection.

Several museums in Austria have also asked his team to review their collections, and a “major museum” in Berlin has also contacted him.

“We know that there are Cambodian artifacts in Germany, France, Italy and Scandinavia, and we are adding them to our database and would like to find out more,” Gordon said.

“In addition,” he added, “we are compiling information on a number of private collections across Europe. We are in research mode at the moment and welcome inquiries from museums and collectors.”

Several museums contacted by DW declined to comment.

What is the legal basis for returning artifacts?

The Convention on the Prohibition and Means of Preventing the Illegal Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, established by UNESCO in 1970, is the main legal basis for countries to request the return of property. .

However, the NGO German Foundation for Lost Arts said in a statement that the treaty “does not apply retrospectively and therefore does not include the peak period of colonialism.”

“Furthermore, such agreements require the involvement of a very large number of countries. Since the 15th century, almost every region of the world has been part of a colonial structure, at least for some period of time.” added.

“The cultural objects and collections brought to Europe therefore come from a variety of different acquisition contexts, each of which may involve specific forms of treatment.”

As a result, some European governments have proposed national laws to determine the fate of artifacts in museums.

Last year, the Austrian government announced that it would propose a law by March 2024 governing the return of national museum collections acquired through colonialism.

At the time, the World Museum in Vienna acknowledged that many of its 200,000 objects, including antiquities from Southeast Asia, could fit this requirement.

But similar laws proposed in other countries have stalled due to political opposition.

European museums, on the other hand, are reluctant to return some of their more valuable collections.

Despite returning hundreds of artifacts to Indonesia last year, a Dutch museum refuses to hand over the remains of the Javanese Man, the first known fossils of the Homo erectus species discovered during the colonial era. did.

But the return of artifacts stolen during colonization could have significant soft power benefits, especially for European countries seeking to expand their influence in regions such as Southeast Asia, scholars say. To tell.

“For Western governments, repatriation of antiquities is ample opportunity to rebuild their brands,” says analyst Cameron Team, who last year published an academic paper on the relationship between repatriation of antiquities and soft power in Cambodia.・Mr. Shapiro stated.

“These repatriations are a show of good faith, a commitment to international law, a symbol of a willingness to recognize and right the wrongs of the past, and a stepping stone to improved relations with foreign governments and peoples. ‘ he added.

Netherlands apologizes for involvement in historic slave trade

A draft resolution submitted to the European Parliament’s Development Committee in December called for the EU to “encourage a concerted effort to recognize, address and redress the persistent effects of European colonialism on social and international inequalities.” “There has been no significant effort made,” he said, while also calling for the creation of a permanent agreement. Her EU institution on restorative justice.

However, some European governments are attempting to explicitly link the return of stolen artifacts with a remorse for historical colonization.

Last year, a month before two Dutch museums returned looted art to Jakarta, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte formally apologized for the Dutch occupation of Indonesia.

Gunay Uslu, the Netherlands’ secretary of state for culture and media, said at the time that “now is the time to look to the future” and that the return would lead to “a period of close cooperation with Indonesia” in research and academic exchanges. added.

According to Shapiro, if European museums return more of their collections, it would be “a monumental step toward a larger soft power strategy, especially in regions where anti-colonial sentiment appears to remain.” “It will be.”

But it added that if Europeans want to win the same praise as the US in Southeast Asia for the return of artifacts, they will need to “make a more public display of effort and be willing to cooperate” with government investigations in the region. Ta. .

[ad_2]

Source link