[ad_1]

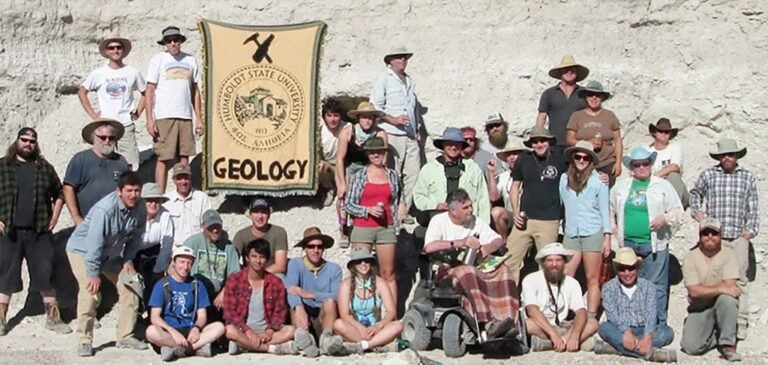

Humboldt Geology students and alumni participate in the 2014 Pleistocene Friends field trip. (contribution)

I had no intention of going into science. When I was in my early teens, I wanted to be a jockey, but I firmly believed I would never weigh more than 100 pounds. I quickly surpassed that weight limit and switched my interests to high school theater. Theater beckoned, but I had no acting talent. I took math for four years because my parents said I should, but I never talked about my math grades because I didn’t want anyone to think I was a nerd.

I arrived at UC Berkeley in the fall of 1964. Like many freshmen, I knew little about the major. I have little recollection of the class I took other than the excitement of the free speech movement spreading across campus at the beginning of that semester, convincing me that we could change the world.

At the time, Berkeley had a wise policy of not making major declarations until the junior year. I dabbled in the humanities, tried journalism, and considered teaching until I decided I didn’t like talking to strangers and took the dreaded ed course. I loved art history, but couldn’t find a viable career path. Science was compulsory and I took Botany the first year, then held my nose and chose Geology at the beginning of the next year.

I don’t know what I was expecting. I grew up thinking of geology as a dry, dusty field where interesting things were discovered years ago. Have you ever been surprised? Two things came together to create a life-changing experience. At first I was an instructor. Professor Howell Williams is a volcanologist who solved the Crater Lake explosion in the 1940s. It was his last year as a teacher and, as a result of an argument with his dean, he was assigned to the “Sports for Jocks” class.

Williams’ response to what he saw as punishment was to teach it like an introductory major class. Many of his 600 people in the class hated it. It was nothing like the easy “A” they were expecting. For me, I had never seen Earth before, so it was great to see a new planet revealed. He emphasized that visualization, aesthetics, and imagination are as important as data and algorithms in understanding geological processes.

The second factor is the geoscience revolution. 1964 was the dawn of plate tectonics, an idea Professor Williams had from the beginning. Only a few people accepted it at the time, but he gave us a sample of the arguments for and against. This was by no means a dead discipline. It was changing before my eyes.

Perhaps this was an area worth exploring further. Is it possible for him to switch to physical science in the third semester after starting his university life?The next semester, he cautiously enrolled in chemistry and calculus I. I was fine.

In my junior year, I declared I would major in geophysics. Why not geology? At the time, Berkeley did not allow women to participate in field camp, the culmination of geology majors. Some women circumvented this requirement by finding outdoor camping on other facilities, but this practice was not encouraged. There was a lot of discussion in geophysics about plate tectonics, which seemed fine to me.

Microscopy, chemical analysis, remote sensing, seismology, and many other new technologies continued to open new doors and further questions. I enrolled in graduate school thinking that I might be able to contribute something. In the end, it was difficult to finish the paper because there were still so many unanswered questions to address.

At Humboldt, I learned that my journey into geosciences was not that different from the students I worked with. Like me, most people switched after taking geology classes to fulfill GE requirements. Geology programs across the country are similar. Geology is rarely offered in high school, and almost never as a preparatory course for college. For students who fall in love with the field during their junior or senior year of college, it’s often too late. Catching up on prerequisites can be a pain, and many schools make it difficult to change majors late in the game.

In 2008, I participated in the NSF-sponsored Geoscience Literacy Project. Our challenge was to define what everyone should know about our home planet and why it’s an interesting field. We spent three months with him and he came up with nine “big ideas” to understand why Earth science affects you and your activities affect the Earth. The three things that interested me most were:

• Humanity depends on the earth for resources. Everything that sustains life, such as water, air, food, fuel, building materials, and electronic equipment, is related to the global environment.

• Natural disasters pose a danger to people. Earthquakes, floods, storms, droughts, and climate change are the result of Earth system processes.

• Humans greatly change the earth. Our activities change ecosystems and climate, exacerbating our exposure to natural hazards.

The Earth Science Literacy Project was expected to increase interest in Earth Science education at both the K-12 and university levels. Unfortunately, this is not the case. The American Geosciences Institute tracks U.S. college enrollment and employment.Both undergraduate and graduate enrollment have steadily declined since 2015. Demand for jobs has increased throughout this period, and it is true that as of 2021, a strange 96% of geoscience graduates with degrees up to 2014. -Adopted in 2018.

All of these trends are also at play in Humboldt. We live in one of the most dynamic parts of the United States, where natural disasters remind us of their importance every year. Developing offshore wind power requires an understanding of geological forces. Earth science and geoscience literacy are an essential part of decision-making, both as individuals and as communities. Still, UC Humboldt’s geology department is shrinking.

When I arrived in 1978, we had nine tenured faculty and four adjuncts. Currently, he has four tenured positions and less than one full-time position. I retired from his teaching position in 2015, but his position never changed. The natural disasters course I taught every semester in his 2000s is only offered occasionally. Last week I learned that the BA in Geology is about to be phased out (BS will continue) and that another 5% reduction in staffing is on the horizon. This is especially frustrating given the sector’s growth post-COVID-19.

After Humboldt became a UC graduate student, people told me what an exciting opportunity it was for geology. Unfortunately, geosciences is not recognized as an important part of the new university vision. It might take a little hoopla to remind everyone that Mother Earth matters and that we all need more geoscientists.

Note: For more information about why big ideas and earth science are relevant, see https://scied.ucar.edu/sites/default/files/2021-10/earth_science_literacy_brochure.pdf

Lori Dengler is professor emeritus of geology at Cal Poly Humboldt and an expert on tsunami and earthquake hazards. Have questions or comments about this column, or would you like a free copy of the prep magazine Living on Shaky Ground? Leave a message at 707-826-6019 or email Kamome@humboldt.edu.

[ad_2]

Source link